Updated on December 6, 2022

Posidonia flowering : an event full of hope

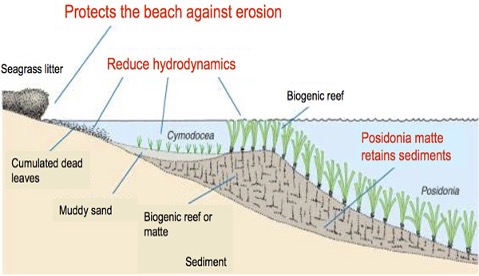

Posidonia oceanica is an endemic species from the Mediterranean Sea. This large and slow-growing seagrass develops on rocks and sandy bottoms in clean water from the surface to over 40-meter depth (Hemminga and Duarte 2000). Posidonia constitutes characteristic formations called “Posidonia meadows” or “Posidonia beds” which are very important habitats in the marine ecosystem. These extensive meadows provide habitat and nutrition for many species of fish, crustaceans, molluscs, bryozoans, as well as for many species of plants. The leaves of Posidonia reduce the speed of the current protecting the beach against erosion and the meadows also produce large quantities of oxygen through photosynthesis, helping in the absorption of CO2 emissions due to its high carbon fixation capacity. Due to its importance Posidonia meadows constitute a habitat protected by the European law (Priority Habitat in the Habitats Directive 92/43/EEC). Sadly, in recent decades Posidonia meadows are facing a regression, mainly due to trawling and anchoring, two activities that cause serious damage to the meadows.

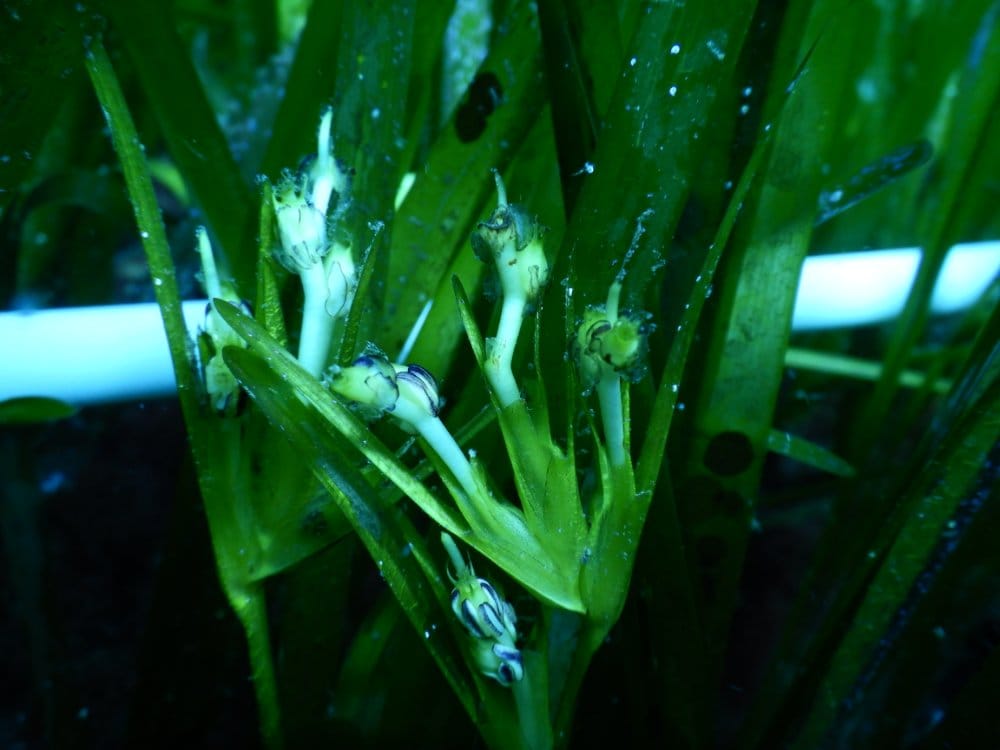

Posidonia propagates mainly via vegetative reproduction through rhizome elongation and cuttings. However, Posidonia can also display sexual reproduction which increases genomic recombination, favouring adaptation and enhancing species resilience to environmental change. Therefore, we can say that Posidonia can also flower under the sea, this event occurs infrequently during autumn every five to ten years. The flowers are hermaphrodite, i.e. both male and females at the same time. The fruits require 6 to 9 months to ripen. Between May and July, they drop off, float for a while and end up washing up on beaches.

Last year, project M.A.R.E. participated in a survey to collect information and samples of Posidonia on behalf of the Italian Ministry of Ecological Transition.  This survey was conducted in the Marine Protected Area Regno di Nettuno, which embraces the islands of Ischia, Procida and Vivara. While conducting this activity in late October and November we observed a big event of flowering that was happening not only in Regno di Nettuno but also in Punta Campanella, as we discovered later. The measurements we took in Regno di Nettuno indicated a high density of flowers as we found 10 to 30 flowers of Posidonia in quadrats of 40cm x 40cm. This abundance of flowers had as result a big production of seeds, that ended up washing up on beaches in great quantities, and this is what we will be observing next spring in the Sorrentine coast. We encourage you to open your eyes during your beach walks to observe this unusual phenomenon. Stranded in the beach you can found the Posidonia fruits so-called “sea olives”.

This survey was conducted in the Marine Protected Area Regno di Nettuno, which embraces the islands of Ischia, Procida and Vivara. While conducting this activity in late October and November we observed a big event of flowering that was happening not only in Regno di Nettuno but also in Punta Campanella, as we discovered later. The measurements we took in Regno di Nettuno indicated a high density of flowers as we found 10 to 30 flowers of Posidonia in quadrats of 40cm x 40cm. This abundance of flowers had as result a big production of seeds, that ended up washing up on beaches in great quantities, and this is what we will be observing next spring in the Sorrentine coast. We encourage you to open your eyes during your beach walks to observe this unusual phenomenon. Stranded in the beach you can found the Posidonia fruits so-called “sea olives”.

But why this happens? Studies of the seagrass Posidonia suggest that flowering is mainly related with high temperatures, and indeed, Ruiz et al. (2018) found in an experimental study that heat exposure can serve as primary trigger of flowering in Posidonia. Normally, very high temperatures stress Posidonia, inhibiting the growth. Therefore, for a sessile plant, seed production is the best escape strategy to overcome stressful conditions. Factors other than environmental temperature, including genetic, physiological, and age-related factors, may likely be involved in determining the flowering. Despite not all the factors affecting this phenomenon are well understood, Posidonia flowering seems to be a hopeful strategy in the global warming context. There is considerable room for optimism as it appears that our beloved seagrass can respond to increasing temperature in more plastic, more complex and potentially more resilient ways than previously imagined. Despite there is no scientific evidence published of this extraordinary event that happened last year, experts as Gabriele Procaccini from the Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn (Naples) confirmed that the abundance of flowers is something that has never seen in this area. If you are interested in knowing more about Posidonia and this extraordinary event, we encourage you to watch the seminar “Le Praterie sommerse del Mediterraneo” from the Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn.

Claudia Gaspar García

Bibliography

Hemminga, M. A., & Duarte, C. M. (2000). Seagrass ecology. Cambridge University Press.

https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/seagrass-ecology/53A7465F196885C57CF1977DF226C77D

https://books.google.it/books/about/Seagrass_Ecology.html?id=uet0dSgzhrsC&redir_esc=y

Luque, Á. A., & Templado, J. (2004). Praderas y bosques marinos de Andalucía. Junta de Andalucía, Sevilla.

https://uicnmed.org/bibliotecavirtualposidonia/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Praderas-y-bosques-marinos-de-Andalucia_Praderas-marinasF_Intro-y-Posidonia-oceanica_Part1.pdf

Ruiz, J. M., Marín-Guirao, L., García-Muñoz, R., Ramos-Segura, A., Bernardeau-Esteller, J., Pérez, M., Sanmartí, N.,Ontoria, Y., Romero, J., Arthur, R., Alcoverro, T. & Procaccini, G. (2018). Experimental evidence of warming-induced flowering in the Mediterranean seagrass Posidonia oceanica. Marine pollution bulletin, 134, 49-54.

https://www.szn.it/images/pubblicazioni/97._Ruiz_et_al_2017.pdf

Procaccini, G. (2022, June 9). Le Praterie sommerse del Mediterraneo [Video file]. Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn, Napoli. Retrieved from

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KhEXIdFlnJQ